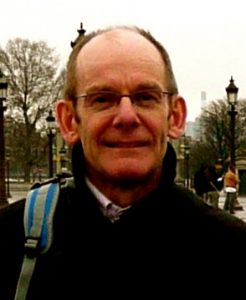

Edward Hughes is Professor of French at Queen Mary University of London. He was joint-winner of the Franco-British Society Literary Prize 2016 for his book ‘Albert Camus’, published by Reaktion Books.

Edward Hughes is Professor of French at Queen Mary University of London. He was joint-winner of the Franco-British Society Literary Prize 2016 for his book ‘Albert Camus’, published by Reaktion Books.

Can you first please briefly go through your education and career?

I was born in Belfast and started university there in 1971, taking a BA in French and Spanish. On graduating, I wanted to do a PhD on the work of Marcel Proust and was encouraged to stay on at Queen’s University Belfast because there was a Proust specialist in the French Department, Professor Richard Bales. I worked very happily under his supervision and completed the thesis in 1979. After a temporary, one-year lectureship in Belfast, I came to London in 1980 to take up a lectureship in French at Birkbeck College. I taught there for eleven years before moving to Royal Holloway, University of London, where I worked for fifteen years. In September 2006, I came to Queen Mary University of London.

Were you a Professor of French language or did you also teach other disciplines?

In each of my posts, I have taught French language, French culture and French literature. I teach predominantly twentieth-century French literature and some contemporary French literature. An additional area of interest for me is Algerian francophone literature.

Can you explain your connection to France? When did your life become Franco- British/Irish?

My introduction to things French took place when I was a pupil in secondary school back in Belfast. I had an outstanding teacher of French, James Frazer. Every year at the end of the school year, he would head off to France. He would come back two months later at the start of September and he would bring back with him a taste of France, so to speak. He was an extremely gifted teacher and he taught me a love of the French language, French culture and French literature.

When I went to university I was again extremely fortunate to have brilliant teachers. I have mentioned Richard Bales who supervised my PhD. When I was an undergraduate student of French, the Professor in the Department was Henri Godin. His teaching was really inspirational. So it was my teachers who steered me towards France during my teenage years and into my early twenties.

As part of my PhD, I carried out research in the Cabinet des Manuscrits at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris. This was extremely important in terms of my development and was a very formative time. And of course when I started teaching in London, the opportunities to travel to France became more frequent. I remember the first time I took the Eurostar, a few weeks after it opened.

That is how my contacts with France began and they have carried on in academic terms. For example, I am an associate member of the Équipe Proust, a research team based at the École Normale Supérieure in the Rue d’Ulm in Paris. I am in regular contact with researchers there. I sometimes attend conferences there and have contributed to some of the publications of the Equipe Proust. Connections such as this are very important for me.

Is your research interest still focused on Proust?

I still do research on Proust but my research interests also reach beyond that. In recent times, for example, I have started working on a project which looks at the depiction of working-class culture in twentieth-century French literature. I have been especially interested in the work of the contemporary French philosopher Jacques Rancière, who has done important work in that area. I have been trying to look at Rancière’s work to see ways in which one can connect that to the understanding and analysis of modern and contemporary French texts.

What are the benefits of being bilingual in French and English?

When someone speaks another language, many doors open up. Another way of looking at the question is this. If I go to a country where I do not know the language, for example to Germany, where I went to visit my daughter who was a student there some time ago now, not having the language made it really difficult for me to make any kind of connection with the local people. German people were very generous in speaking English to me but not having the language has to leave one a bit on the outside.

If one is bilingual English and French, it means that when one goes to a Francophone country, one can engage fully not only with people individually but with the life of the country, its political, social, cultural and literary life. All of that is extremely rich.

The doors can open not only in terms of one’s work but also through the contacts that one has with individual people. Over the years, for me and my family, the link to France has been a source of great richness. We have friendships there going back more than thirty years.

There are many French students in the UK and fewer Britons studying in French universities. As a university teacher in a French department, how would you encourage British students to study abroad? What can be done to balance this unevenness?

Studying abroad for modern languages students is crucial for their development. Certainly for students who are taking a BA in French, the year abroad is absolutely vital. It is a great opportunity to have contact with the language and culture, and often with cultural differences. But also for students not on modern language programmes, the mobility that comes with the Erasmus scheme, for example, has so much potential, given the world we live and work in. Widening perspectives is so important. Take just one, small example. One can read the national press here. One then reads the press in another country to see others’ perspective on events and the world. One is instantly given exposure to other ways of seeing. It has to be beneficial.

How do you perceive French and British cooperation in the university research field?

The collaborations between the two systems are extremely important. And of course collaboration is becoming more important given the political conjuncture that we are now facing. We know how much how the Erasmus scheme has facilitated staff mobility. This is now facing serious problems with Brexit, but there are many groups in the UK that are very actively involved in promoting links with France. Take just one example that I know very well, the work of the Society for French Studies. The society is based in the UK and Ireland but when we have our annual conference the keynote speakers will be drawn invariably from the French university system or will be contemporary French writers. These contacts are very important.

Here in London we have colleagues at the French Embassy who are responsible for university cooperation. This is vital not only for language studies but in areas such as law, science and business. The capacity for collaboration is extremely strong.

Postdoctoral teachers play a crucial role in the UK university system. Looking fifteen, twenty years down the line, they will be the leaders of our university system. Over a fifth of them are EU nationals. Again, this kind of collaboration is essential and indeed the need that the UK university system has for this collaboration with continental Europe and its various national university cultures is a crucial factor. The last thing we would want is to accept that because Britain is leaving the EU, we as a country should be thinking that our university system should somehow retreat from those important contacts that we have with European university systems. The need for connection and collaboration is becoming all the stronger with Brexit.

You often write about French culture, literature and socio-political questions. What are your main areas of interest?

As I mentioned before, my most recent project focuses on the ways in which French literature and French thought of the twentieth and twenty first centuries represent working-class culture, how it captures the so-called ‘voices from below’. Are these subaltern voices ‘heard’, as it were, and are they present in the literary context or in philosophical debate? Over the years I have done a good deal of work on Marcel Proust and on Albert Camus. I have worked also, within the Algerian context, both on French-Algerian literary production and on post-Independence, francophone Algerian authors. I have published recently on Mohammed Dib, who was a leading figure in francophone literature of Algeria in the second half of the twentieth century and into the beginning of this century. One of the things that interests me about Dib is the plurality of perspectives in his work. He had an intensely Algerian phase, when he addressed pressing issues to do with his country’s troubled twentieth-century history. But Dib also looks beyond that and we see his later texts engaging with conflicts and debates affecting various parts of the world. He is an important voice in world literature.

What modules do you enjoy teaching at university?

I enjoy teaching final-year undergraduates the exercise of ‘Commentaire Littéraire’. We look at a range of literary texts, with class discussions conducted wholly in French. I find that to be a really engaging teaching experience, as well as a challenging one. I also teach first-year students who take our French Foundations module. I work with them specifically on Mai 68. With the second-year undergraduates, I enjoy delivering a module entitled ‘Out of Place’: Literature and Dislocation. We look at marginality and at cultures of dislocation and we explore the ways in which those issues are addressed and represented in literary texts. In the final year of the BA, I also offer a module that focuses on the work of Marcel Proust. It’s a challenging module for students because the text is complex and quite dense at times. I sometimes ask myself if having specialist knowledge of an author is an advantage or a disadvantage in the teaching situation. Perhaps knowing a bit less about an author can be better when trying to introduce that author to students. I think it can work both ways. But coming back to your question, I like to be in contact with first-, second- and final-year undergraduate students. That way, you see their development and the directions they are taking.

Are you familiar with the career prospects of former French language students in UK universities?

We recently held a Careers Evening where graduate students came back to share their experiences of the world of work. Many of our BA French graduates work in London in a variety of fields. For example, they might work in journalism or administration or public relations. When I graduated, it was a different time and a different culture and those with a BA in Modern Languages would often go into teaching. Now, especially in a city like London, the opportunities and career options are diverse. Accounting, translating, advertising, finance, law conversion courses… the spectrum is wide. One of the key skills of modern language students is their communicational abilities. Languages and language learning are all about communication.

When and why did you decide to write a book on one of France’s most high-profile writers, Albert Camus?

Camus is someone I have been interested in for a long time. A few years ago, a publisher invited me to think about writing a biography of Camus. The big biographies of Camus have been written by other people (Olivier Todd, most notably) but I hope that the slant on Camus that I offer provides readers with good points of access to the writer. I was really fortunate and delighted to get a Fellowship from the Leverhulme Trust for the academic year 2013-2014. That was vital for me. It gave me a full year to work intensively on the project and meant I was freed from my teaching and administrative duties here at Queen Mary. It was a very fulfilling experience. The publishers I was writing for, Reaktion Books here in London, were very supportive and once I produced the manuscript, things went ahead very promptly. The book came out in 2015 and I was honoured to be the joint winner of the Franco-British Society Literary Prize 2016, along with David Loosely for his book on Edith Piaf.

Interviewed by Eugenia Esteva Vegas

Franco-British Portrait Gallery